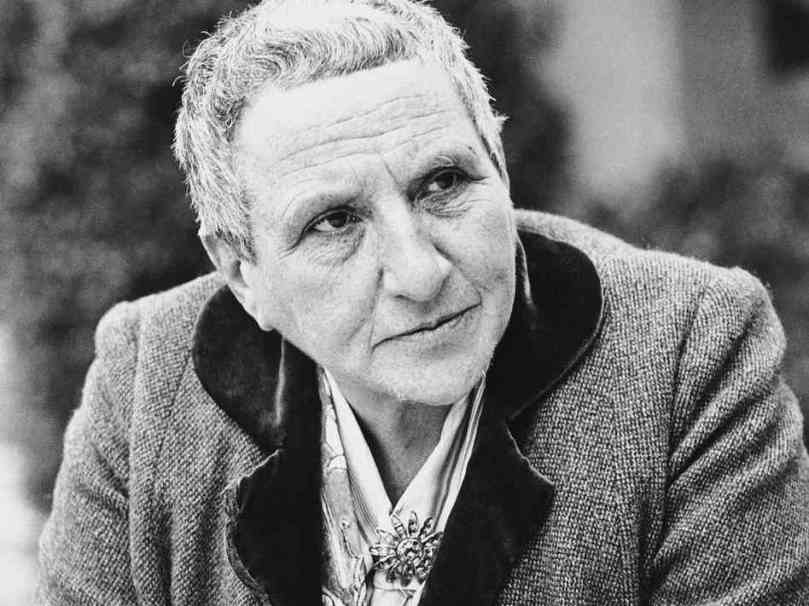

Gertrude Stein, Our Author

“Perhaps this is because language, unlike paint, does not simply become ‘beautiful’ once a style is widely accepted. In any event, we might consider ourselves fortunate to be able still to feel what is shocking and irritating in modern writing. It reminds us that we are in the presence of something that still feels genuinely new and different.”

~Jonathan Levin (on Stein’s writing)

Gertrude Stein: America’s First Avant-Garde Dramatist

Gertrude Stein was born in Pennsylvania in 1874 to wealthy German-Jewish immigrant parents. In 1877, when Gertrude was just three, her family moved to Europe and lived in Vienna and Paris. A year later, the Stein family returned to the United States, taking up residence in Oakland. Stein’s mother died of cancer in 1888 and her father passed away just three years later in 1891. Before Stein had turned eighteen, she and her siblings were orphaned. Fortunately, they were well provided for and lived for many years off their considerable inheritance.

Stein attended Harvard/Radcliffe College from 1893-1897 and completed significant research in psychology. She followed her time at Harvard with study in medicine at Johns Hopkins, but she did not earn a formal degree from either university. In 1903, she moved to Paris with Alice B. Toklas, the woman who would become her lifelong partner. Her brother Leo had moved there a year earlier and was active in the burgeoning Paris art scene. Their apartment at 27 rue de Fleurus became a destination for many significant artists of the time, including Picasso, Matisse, and Renoir, not to mention literary figures as significant as Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Djuana Barnes, James Joyce, and Thornton Wilder. The Steins were avid collectors of modern art, and the gatherings at their apartment became legendary.

Stein scholar Sarah Bay-Cheng, in the introduction to her influential book-length study Mama Dada: Gertrude Stein’s Avant-Garde Theatre, called Stein “the first genuine avant-garde dramatist of her country” (1). Stein’s approach to writing drew both from her study of psychology at Harvard, where she conducted experiments into Automatic Writing, or writing without conscious intent to produce meaning. She and her fellow researchers proposed the idea that writing was a physical activity that one could complete with muscle memory rather than intellectual intent.

Her interest in Automatic Writing paired well with her fervent interest in Modern, Cubist art, which explored representing motion by showing several “frames” of movement on one canvas. These twin interests seem to have contributed to her distinctive style of writing that rejects coherent plot lines and the concomitant simplistic emotional manipulation frequently used in Naturalist theatre of the late 19th Century. Stein’s language seems more like an exploration of sounds, which strips words of their usual meaning.

If Stein’s words remove their usual meaning, the question then becomes, what do they mean? Or mean to us? The stripping of meaning was serious business to the Dadaists and other Modern artists. Bert Cardullo asserts in his introduction to Theatre of the Avant-Garde, 1890-1950, “Coherence had become such a despised characteristic by the early twentieth century, however, that many dramatists tried to eliminate it, just as the so-called literary or narrative element had been removed from much painting and sculpture” (19). At times, the language may seem like pure nonsense to us, but if we can accept this as an intentional attempt to open up a different way of thinking and interacting with a performance, I think you may find Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights an exciting experience unlike anything you have seen in the theatre. For the artists creating work in the wake of the mechanized devastation of WWI, the world itself was making no sense. These artists effectively asked, how can we possibly continue on as if the world makes sense, pretending that such brutality did not take place? Artists like Stein were questioning everything, even the very language we use in our daily lives.

Shelley Orr, Co-Dramaturg